Why authorization architecture is probably fragile

/assets/post241022/audio.mp3

Authorization is a critical component of application security, and it’s becoming increasingly challenging to implement as application use cases evolve. In my work, I was lucky enough to tackle this challenge, where the requirements involved organizational hierarchy, an invitation system, and access restrictions.

Initially, we built a basic authorization system in PostgreSQL, but the design quickly fell apart as the requirements evolved. We had to account for scenarios like temporarily accessible records or records accessible only by specific users. So we decided to explore other solutions.

Google published a white paper explaining their internal authorization system, Zanzibar, which inspired many open-source implementations. Out of these, we decided to go with SpiceDB. The idea of Zanzibar is a distributed authorization system that services can speak to, and let it know when records are created/updated/deleted by who. Later, you query the system to get an authorization decision.

In many cases, authorization checks are performed within the backend application code, separate from the data they are meant to protect. This approach has downsides, creating opportunities for mistakes and inconsistencies between services with varying degrees of security interacting with the same data.

This post highlights some of the flaws in current authorization models. I’ll use a hypothetical Dropbox-like system as an example to illustrate the risks of relying solely on application-level checks, which can leave serious security concerns.

To illustrate these points, let’s look at a typical CRUD application model and focus on two specific endpoints:

POST /fileThis endpoint creates a Dropbox file record and returns its ID.GET /file/{ID}This endpoint retrieves a file record by its ID.

Each of these endpoints would require distinct authorization actions.

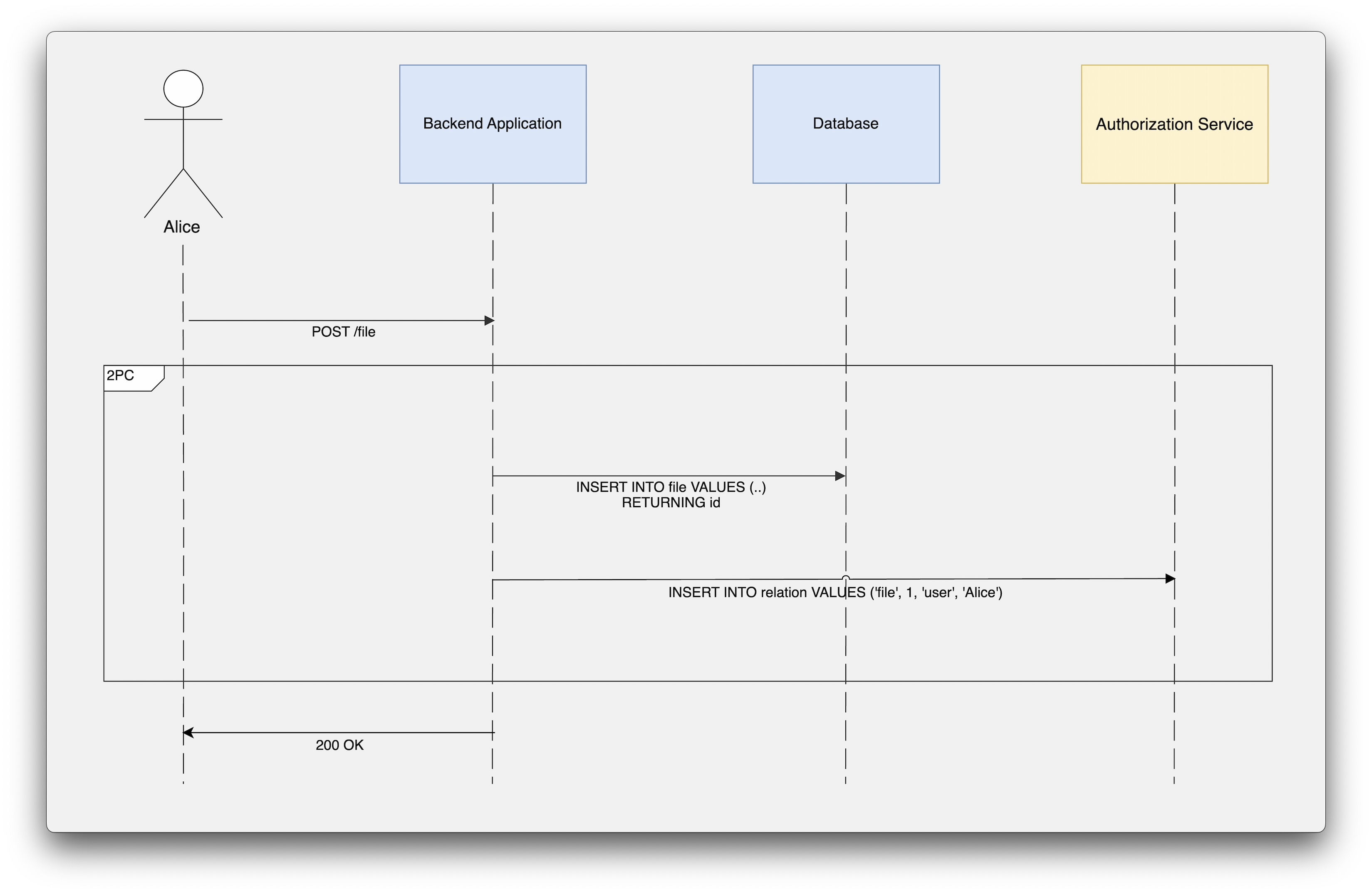

Create a file record

In a create scenario, the backend application creates a record in the domain database and updates the authorization service to associate the record ID with the user ID.

This is the part where the application needs to notify the authorization service about mutations. It’s up to the application to ensure that the writes to the domain database and the authorization service are atomic. This means that if writing to the authorization service fails, the write to the database should be rolled back.

In this example, we are using a two-phase commit approach. However, an architecture might also implement Change Data Capture (CDC) to capture write events to the domain database and maintain tuple relations in the authorization service. Alternatively, in CQRS architecture, the application could send authorization commands that are then recorded in the authorization service. Regardless of the approach, the core problem this post aims to highlight remains the same: Application-level authorisation checks could be dangerous.

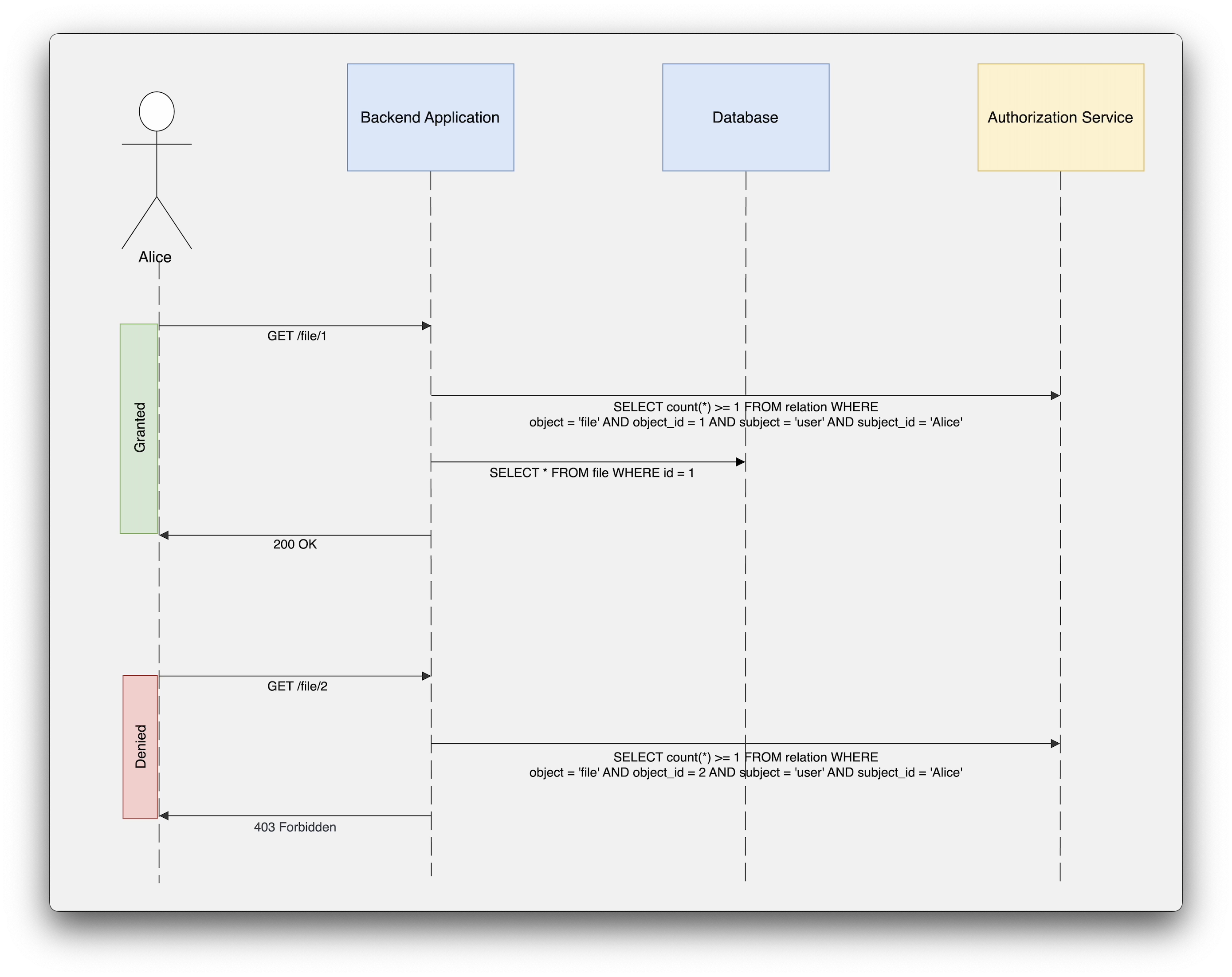

Reading a file record

To read a single file record, the application first checks permissions by asking the authorization service whether a given user is on the list of users allowed to perform read action on that record.

Again, the application is responsible for correctly interpreting and enforcing the authorization service’s response. In the first call, Alice wants to read the record with ID 1, and the authorization service permits that access. However, if the application has a bug in processing the authorization decision, it could incorrectly reject the call.

The second example illustrates access denial, where Alice requests record ID 2. In this case, the misinterpretation of the denial is even worse where the application might query the database and return the result, even though the authorization service has denied the access request. This inconsistency highlights the risks associated with relying on application-level authorization checks.

Is this secure?

On the AuthZed landing page, the creators of SpiceDB, they demonstrate a permission system with a spaceship request authorization decision to land on a planet. In the example, one spaceship is denied landing, and the other is granted access.

However, if the spaceship has a bug in its code, it might not land when it was granted permission, or it might land even when the authorization service denied its access request. This discrepancy demonstrates the dangers of relying on application-level checks, as an application might deliberately bypass the authorization decision entirely. In our Dropbox example, if we decided to build another backend service in addition to what we currently have, that new backend application would not only need to re-implement authorization checks but also ensure they are implemented correctly and match the behaviour of the existing system.

Whether this design is secure depends on the domain of the problem we are trying to solve. In a scenario involving strict regulatory requirements, and we keep the permission checks within the application—where the application can choose whether or not to abide by those checks— I think this approach is undeniably insecure.

What are we guarding?

We use an authorization service to keep data secure and ensure that only those with the proper permissions can access it. In other words, our goal is to prevent unauthorized access to sensitive records. So why aren’t we placing boundaries directly around our data? Our hypothetical Dropbox backend application performs the authorization checks and then queries the database based on those decisions. The protections are only around the backend application, not the data itself.

To put this in the context of today’s era of complex access control requirements, let’s say our Dropbox implementation consists of the following permissions:

- Read and write access by the creator of a file.

- Read and write access by users who have read and write access to the parent folder.

- Invite users with read-only permissions.

- Invite users with read and write permissions.

- Invite an organization to a file/folder, and inherently, all users within that organization get the specified permissions.

Some databases support Row-Level Security (RLS), a policy-based security layer at the database level, and policies are evaluated at query time. However, these RLS implementations often lack the advanced relational capabilities that Zanzibar-inspired products are solving. RLS is designed mainly in the context of database SQL statements. This is an example of how RLS looks:

CREATE POLICY file_owner_can_read ON file

AS RESTRICTIVE

FOR SELECT

USING ( current_user = file.owner_user_id )

This policy appends an implicit WHERE clause to any SELECT query on the file table, filtering those records where the owner ID matches the current user.

Now, let’s say our permission requirements evolved, and we need to allow a group of users from a specific team to be able to read a given folder, and part of these users have read and write access, allowing them to modify files in that folder. Imagine how complicated it would be to create policies for every possible read situation, or how impossible it would be to allow for a nested organizational hierarchy. There’s a clear need for a database-level authorization system that can cope with today’s (and hopefully future) requirements. This could be narrowed down to what Zanzibar addresses: finding a relationship chain between a record and a user.

Conclusion

In summary, authorization is a complex and essential aspect of application security. Various models exist, including role-based, attribute-based, and relation-based access control. A significant challenge across these approaches is the difficulty of implementing robust authorization mechanisms directly around the data we’re trying to protect. While application-level checks provide some security, they can introduce vulnerabilities if not handled carefully.

I am very passionate about authorization and identity and access management. If you have questions or would like to discuss this further, please feel free to reach out.

Where to go from here

- Take a look at PostgreSQL Row Level Security.

- Read Zanzibar White Paper, or a version that is annotated by AuthZed.

- Read the AuthZed explanation for Zanzibar, and Relation-Based Access Control.